Sell Less, Earn More: Using Scarcity to Boost Revenue

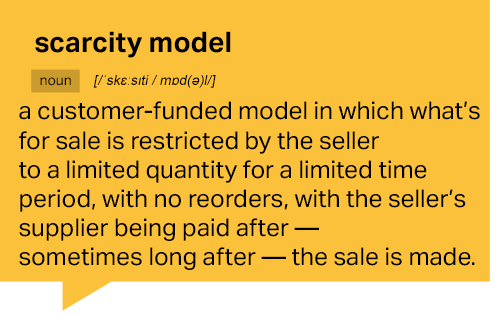

The scarcity model is perhaps the most ingenious out of the five types of customer-funded models since it allows you to earn more from selling less.

That’s music to mid-market founders’ ears, I find. This tactic also takes advantage of the fact that retailers, among others, typically do not have to pay their vendors upfront.

But their customers do – cash or credit card, please!

The model is also, perhaps, the most difficult to pull off successfully, as we’ll soon see. While the scarcity model can generate lots of customer cash, some have found it difficult to make scarcity profitable over the long term.

Here, we will investigate why some companies only achieved short-term success with scarcity models, and how others found innovative ways to use this customer-funding method to their advantage.

Perhaps you can, too!

Creating A New Category Of Retailing

With Scarcity

Scarcity models are nothing new. High-end designer apparel and other luxury brands have been using scarcity to portray exclusivity for years — you won’t find Prada or Gucci on every street corner.

At one point in time, scarcity for these high-end brands was achieved through limited quantity.

Then, vente-privee.com entered the picture with an ingenious new way of using scarcity. They found a way to make fast sales while solving overstock problems for their suppliers. Vente-privee.com was founded by Jacques-Antoine Granjon and his seven business partners.

Vente-privee.com was founded by Jacques-Antoine Granjon and his seven business partners.

Prior to founding the e-commerce company, the team already had years of experience selling fashion apparel manufacturers’ overstocked inventory through a variety of underground events that would not disrupt the carefully honed brand images of their upscale suppliers.

In 2000, Granjon was inspired by the arrival of e-commerce. Connecting the dots between his experience in selling overstocked merchandise through events with the internet’s ability to create a virtual store, Granjon pioneered the online flash sale model.

Vente-privee launched in France in January 2001. The simple concept was based on the French phrase vente privée, which means “private sale.”

Here’s how their model worked.

From time to time, after securing a deal for a vendor’s overstocked or closeout fashion merchandise, vente-privee would send an email to their members informing them of a “private sale event” happening in 48 hours. Two days later, the limited quantity merchandise would go on sale, but not for long. The sale would last for just three to five days, with the goods priced 50-70% below the designer brands’ retail price.

The message was simple. “Buy now, before it’s gone.”

Vente-privee members would enjoy a huge discount on designer brands and the brands could get rid of unwanted inventory in an exclusive manner that didn’t tarnish their image in the fancy shops on the Champs-Élysée, because the discounted price was only available to members and not the public. After the sale, sometimes as many as 60 days after the sale, vente-privee would pay its vendors for the items sold.

After the sale, sometimes as many as 60 days after the sale, vente-privee would pay its vendors for the items sold.

But the customers had paid with the credit cards at the time of purchase! By having their customers’ cash in their hand before having to pay their vendors for the inventory, vente-privee had the funds to expand rapidly.

Just two years after its inception, vente-privee was selling more than 200,000 items each day to its 1.8 million members across eight European countries, collecting revenues amounting to €1.6 billion in a year. By 2013, they had grown to 2,100 employees worldwide.

Granjon’s ingenious idea of applying scarcity in an online flash sale format transformed the method of selling end-of-season, excess, and overstocked styles for high-end designer brands. Unsurprisingly, other merchants began imitating the flash sale format that vente-privee had pioneered, and an entire new category of retailing was born.

Replicating The Success Of Flash Sales (But Not For Long)

One of the copycats that attempted to replicate the success of vente-privee’s flash sale model was Totsy, a company focusing on goods for babies and children aged zero to seven at deeply discounted prices.

Unlike vente-privee which relied on customer funding to grow, Totsy raised $5 million in venture capital. Then in August 2012, they raised another $18.5 million. By November 2012, Totsy had more than 100 employees serving 3 million members.

Things were looking bright for Totsy, but not for long. Totsy was using VC money to spend aggressively to expand its member base. Although they rapidly grew in membership, only 10.8% of those who signed up as Totsy members had actually become paying customers.

And of those who did buy something, not as many as Totsy’s founders hoped had come back for more.

The result?

By May 2013, Totsy crashed, laying off all of its employees. Although Totsy’s revenue in 2012 had reached $16.9 million, it incurred $22.9 million in losses.

A similar fate unfolded for Lot18, a company that provided access to high-quality wines from around the globe at discount prices through flash sales. With $3 million in capital added to an earlier $500,000 seed round, Lot18 launched in November 2010.

Like Totsy, Lot18’s early months were promising. They gained 200,000 new members and sold thousands of bottles each week. Their monthly revenue quickly exceeded $1 million. With this excellent start, Lot18 received more funding — first $10 million, followed by another $30 million in November 2011. After that, Lot18 acquired Vinobest, a similar business, just a year after launching.

But then, in January 2012, just weeks after the Vinobest acquisition, Lot18 laid off 15% of its employees. A few months later, four senior executives departed.

By May 2013, after yet another round of layoffs, the company was left with just 36 employees. In addition, both of its co-founders had departed and in July 2013, the company closed its UK office, which it had opened a mere four months earlier.

It wasn’t long before the venture capital and private equity investors who had bankrolled this fast-growing new industry realized that all was not well in the flash sales world, even for vente-privee, which had also taken on external funding in 2007. The funding helped the company expand in Europe: first in Spain and Germany, then in Italy and the UK, and eventually in Belgium, Austria and the Netherlands.

What had gone awry? First, the fashion manufacturers no longer had the huge quantities of excess inventory that they’d had to unload in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007 to 2009.

First, the fashion manufacturers no longer had the huge quantities of excess inventory that they’d had to unload in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007 to 2009.

Second, amid roaring demand from vente-privee’s VC-fueled copycats and others, some manufacturers with no closeouts to sell simply started making goods specifically for the flash sales merchants.

Cheaper fabrics and fewer stitches per inch created the illusion that the flash sales buyers were getting a good deal. But their customers knew better, and the flash sales party ended.

The result?

The industry consolidated, with the bigger players like vente-privee buying up the smaller ones at bargain-basement prices. Even vente-privee was forced to shut down its US division.

Did the VC’s make money, you ask? Apart from Zulily in the USA, which IPO’d in 2013, just one year after raising venture capital, and was sold for less than half its IPO price in 2015, exits of flash sales businesses have been nigh on non-existent.

So can scarcity models work, you are wondering?

They can, but flash sales is not the answer. Read on.

Innovative Ways To Make Scarcity Work And Deliver Customer Funds

Zara, the Spanish fashion apparel chain, found an innovative way to apply scarcity in the fashion industry without relying on flash sales.

They would follow “who’s wearing what” on stage and on the fashion runway, and then copy it very quickly. Something that was worn by celebrities one week on stage could hit Zara stores in just a couple of weeks. However, Zara wouldn’t ever order the same design again.

Because Zara can forecast well, they can control the limited supply in the styles they create. Their customers know this and know that if they see something they like in Zara, they’d better buy it now or it will be gone forever. This scarcity in quantity also encourages young fashionistas to visit Zara often so they don’t miss out on the latest styles they might want.

For Zara, the customer puts down her cash or credit card at the time of purchase, but Zara’s terms with its tightly linked manufacturers are typically 60 days. Zara’s scarcity model means that Zara typically turns its inventory some 12 times each year. So it has sold it all before it has to pay its supplier. That customer cash has funded Zara’s rapid growth.

Outside of the fashion industry, a restaurant in Austin, Texas has figured how to use scarcity to sell their barbecue. The restaurant, Franklin’s BBQ, opens at 11am but when their barbecue is gone — it’s gone. Their customers know that, and they will be queuing up in line starting as early as 6 in the morning.

Their customers are willing to bring picnic chairs and beanbags to make themselves as comfortable as possible while they wait, just to make sure they get the barbecue they want. A recent innovation using a scarcity model can be seen with Revolut, a digital banking alternative that includes a prepaid debit card, currency exchange, cryptocurrency exchange and peer-to-peer payments. Revolut ingeniously combined scarcity with subscriptions, another customer-funded model.

A recent innovation using a scarcity model can be seen with Revolut, a digital banking alternative that includes a prepaid debit card, currency exchange, cryptocurrency exchange and peer-to-peer payments. Revolut ingeniously combined scarcity with subscriptions, another customer-funded model.

In August 2018, Revolut launched Revolut Metal – their new contactless metal card. Only 10,000 metal cards were available and they were reserved for their Premium customers who had to pre-register for the exclusivity of owning one.

In addition to this scarcity, the metal cards were packaged with a £12.99 monthly subscription package that gave their Premium customers exclusive benefits, from free medical insurance to instant cryptocurrency access and cryptocurrency cashback.

By combining scarcity with a subscription to exclusive services, Revolut has not just made more sales by selling less, they have also secured recurring revenue to maximize the customer funds they raise for growth.

3 Important Lessons To Make Scarcity Work In Your Mid-Market Company

How can you make scarcity models work?

There are three important lessons we can learn from the case studies in this article.

First, at the heart of the scarcity model is the truism that the customer must pay before vendors are paid. As I tell the founders and CEOs I work with, “Love thy float!”

Second, we’ve seen that VC-fueled growth in which customer acquisition cost (CAC) is higher than what those customers are worth in lifetime value (LTV) is a fast track to disaster. Just because a customer buys from you twice in her first 90 days doesn’t mean she’s going to do so for the rest of her life! Your LTV calculation may well be wrong!

Last, companies like Zara, Franklin’s BBQ, and Revolut that have found innovative ways to apply scarcity suggest that scarcity models can work under the right circumstances, and almost always, in my experience, without venture capital.

So whether you’re selling goods – like Frank’s BBQ – or services – like Revolut’s digital banking – if you can get your customers to “buy now before it’s gone” while getting favorable terms from your key suppliers, you’ll find your mid-market business suddenly flush with cash.

And that’s the cash you can use to turn your perhaps stable and boring mid-market business into a customer-funded growth machine!